The Victorian Orphan

Why Orphans?

In order

to answer the question of whether the orphans should be regarded as a part of a

standard Victorian family, we first need to understand the existence of orphans

in Victorianism. After reading novels like Jane Eyre, Middlemarch and Great

Expectations, one would probably ask, “Why are there so many orphans in

Victorian novels?” Answering this question requires us to examine mortality

rates in Victorian era. Florence Nightingale conducted research on how to

improve sanitary conditions in hospitals in

Who is a Victorian Orphan?

Our conception of the “orphan” nowadays differs slightly from that of the Victorian Orphan. Although we tend to associate an orphan with an entirely parentless child, a Victorian orphan might have one of the two parents alive or have relatives who have taken the role of caretakers. Perhaps the best example of the latter kind of Victorian Orphan is depicted in Charlotte Bronte’s novel Jane Eyre. When Jane’s father dies, she leaves her only child in the care of her rich sister, Mrs. Reed. Although Jane is presumably being taken care of by her relatives, she would have been deemed an orphan in Victorian England.

Notwithstanding that an orphan might be found in the “good” hands of relatives, his status as an orphan prevailed in society. Ironically, within the orphan’s newfound family, he was often regarded as an intruder. Bronte’s description of Jane Eyre’s stay at her aunt Reed’s house shows the kind of treatment that an orphan might receive from her own relative:“…you are a dependent, mama says: you have no money: your father left you none; you ought to beg, and not to live here with gentlemen’s children like us…” (13). Evidently, John Reed feels that Jane should not be a part of his family, as discussed here further. Also, the character of Pip in Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations serves to represent the typical orphan who falls in the hands of an evil relative; his own sister. Thus, in order to understand why orphans were treated as such, we must first explore the relationship between the orphan and the family in Victorian England.

The orphan v. The Family

It is interesting to note how novels like Jane Eyre

portray the central character as virtuous, standing in contrast with the family,

which is often portrayed as cruel and immoral. Although this might not be

representative of all orphan cases, it sure serves as a window to understand the

relationship between the orphan and the Victorian family. Peters (2000) argues

that the orphan “embodied the loss of the family, [and he] came to represent a

dangerous threat; the family reaffirmed itself through the expulsion of this

threatening difference” (2). Notably,

Bronte’s understanding of this relationship seems to be in concert with Peter’s

idea; John Reed’s treatment stems from society’s fear that the idealized

Victorian family might not reflect the actual Victorian family: as mentioned

above, John tells Jane“…ought to

beg, and not to live here with gentlemen’s children...…” (13).Clearly, John Reed

feels that Jane does not fit into the ideal Victorian family, thus why he emphasizes the

disjunctive nature between the family and the orphan living in the same

household. However, Bronte suggests that Jane betokens all the values that this

family lacks. In fact, Peter

argues that, in a sense, that the family contains “its opposite, in the figure

of an orphan”(23). Further,

Thus, these representations suggest that orphans might had often find themselves living with abusive relatives who seemed to hate the idea of an orphan because of what it represented for society—illegitimacy and the shattering of the ideal Victorian family.

Another possible relationship is presented in Dickens' Great Expectations, where he interposes two very different characters who act as symbols of good and evil. On the one hand, the character of Joe reflects values like humility and friendship; for instance, in the early chapters of the novel, Joe tells Pip, “…you and me is always friends...” (12). On the other hand, the character of Mrs. Joe contrasts Joe’s goodness as exemplified by her abuses to both Pip and Joe. Thus, the orphan is presented as a moral battleground between good and evil; in other words, Pip’s actions and decisions, which will eventually determine his fate, are being influenced by both a positive and a negative figure. As opposed to Bronte’s idealization of the orphan, Dickens does not counterpoise the family and the orphan’s values; rather, he seems to blame society as a whole for setting high standards of “gentlemanliness” that might actually corrupt values like friendship and humility that are inherit in the orphan.

The idea that an individual’s status as an “orphan” within the Victorian realm might actually influence his destiny is worthwhile exploring. Peters (2000) examines the different representations of Orphans in Victorian culture, and he classifies orphans in several categories:

The “traveling” orphan

In some

novels, Orphans were often associated with traveling figures like the gypsies.

Peters suggests that the “gypsies within (albeits on the margins of) Victorian

The criminal orphan

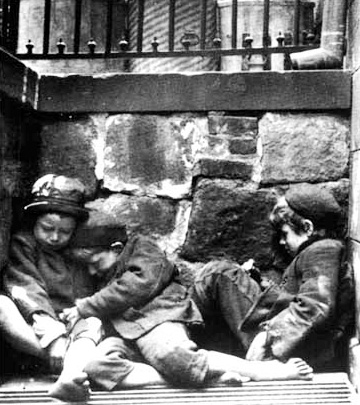

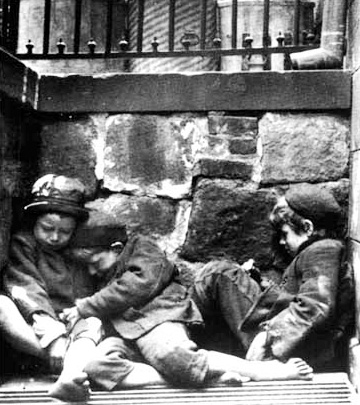

Another representation of the Victorian orphan that is useful in understanding the potential fate of the “poor orphan” who grows up without virtually no family is the criminal orphan. Peters suggests that “the orphaned children of the poor is poignant and emotive one; the state, in failing to provide adequately for the future of these children is failing in the especial responsibility invested in it” (37). Peters introduces Dickens' Oliver twist as the perfect example of an orphan who is victimized by “institutions which are supposed to be taking care of him..” (40). This is perhaps the best example of an orphan who is completely deprived of a family—in fact, Oliver’s trials arise “…primarily from his lack of family…,” which establishes as “a figure of special pathos” for the Victorian reader (40).Moreover, Peters seems to suggest that an orphan’s awareness of his status as an outcast could have actually resulted in the orphan’s wishing for death, “as a relief form the misery and profound loneliness” that his status as an orphan has brought upon him. Notably, Peter suggests that the workhouses, as depicted by Dickens, are “in actuality producing orphans rather than acting as parental substitutes” (40).

Suggestions for Further Reading:

Gordon, Jan B. “Dickens and the transformation of nineteenth-century narratives of legitimacy.” Dickens Studies Annual.. 31 (2002): 203-265 .

WORKS CITED (ORPHANS AND SECRETS)

WORKS CITED (MAIN)